This appeared in Temple Gwathmey Steeplechase Foundation and is reprinted with permission

By Betsy Burke Parker

Editor's note: This story was written in January 2023. It took us some time to get it published. In that time, eventing greats Jimmy Wofford and Kevin Freeman, both featured in this article, passed away. Our thoughts are with their family and friends. We're so fortunate to have had a chance to speak to them before they passed.

Kevin Freeman aboard #5 Morning Mac in the 1971 Maryland Hunt Cup - they finished 3rd (Photo by Douglas Lees)Olympic medalist and steeplechase jockey Kevin Freeman says he had the best of both worlds he occupied simultaneously in the 1960s and ‘70s, explaining that his heart belonged at once to both eventing and jump racing.

Kevin Freeman aboard #5 Morning Mac in the 1971 Maryland Hunt Cup - they finished 3rd (Photo by Douglas Lees)Olympic medalist and steeplechase jockey Kevin Freeman says he had the best of both worlds he occupied simultaneously in the 1960s and ‘70s, explaining that his heart belonged at once to both eventing and jump racing.

“But I loved steeplechase best of all.”

Freeman says that, at surface level, the two bear little resemblance. But dig a little deeper, and there’s a lot the same, with plenty of cross-pollination between the two.

“Including me,” Freeman agrees with a chuckle.

“The common denominator among event riders and race riders comes down to their attitude to riding down to big fences,” says Freeman, now 83. He was on the silver-medal U.S. Olympic three-day event squads in 1972 and 1976, and he was third in the 1971 Maryland Hunt Cup. “You had to love the thrill and challenge of it – to be good at either sport.”

ANOTHER former jockey-turned-eventer, Danny Warrington agrees with Freeman’s assessment. “To go from one to the other, though,” Warrington maintains, “you’ve gotta change your ‘eye’ from running down to a hurdle to setting up for a ‘question.’

“Those jump trainers teach you ‘chipping in is a sin.’ You won’t win too many races that way.”

As strong as the horse and horseman link from eventing to steeplechase, there’s been a long and strong connection at the facility level as well:

Olympic three-day event medalist and 1978 World Champion Bruce Davidson once famously told a reporter that “once you’ve raced, everything you do in eventing is in slow motion by comparison.”

Bruce Davidson (Photo courtesy of Fair Hill International)“Young people today, they don’t even (learn how to) bridge their reins,” Davidson said in a 2017 story in the Chronicle of the Horse. “They don’t understand connection and balance. The horses are being pushed instead of galloping" forward, on their own impulsion.

Bruce Davidson (Photo courtesy of Fair Hill International)“Young people today, they don’t even (learn how to) bridge their reins,” Davidson said in a 2017 story in the Chronicle of the Horse. “They don’t understand connection and balance. The horses are being pushed instead of galloping" forward, on their own impulsion.

The best galloping skills for either sport, Davidson says, come from riding racehorses, whether exercising on the flat track or riding ‘chasers.

Davidson won Olympic team gold at Montreal (1976) and Los Angeles (1984), as well as silvers in 1972 and 1996. He’s won Badminton in England, the World Championships twice and the Kentucky Three-Day event on multiple occasions.

Davidson rode in the Maryland Hunt Cup, twice (pulled up Danny’s Brother in 1975, fifth on Appolinax in 1983. (Douglas Lees photo, right, of Davidson and Appolinax at the 13th fence in 1983) He won at My Lady’s Manor with Stephanie Speakman’s Our Steeplejack in 1984. He was fourth in the 1989 Pennsylvania Hunt Cup with Alletta Bredin-Bell’s Macquarie, a horse he also trained.

“It was a big part of my life, and I loved it,” Davidson said in the Chronicle article. “Back in the ’70s and ’80s almost everybody (in the mid-Atlantic region) point-to-pointed.”

Every member of the silver-medal-winning 1972 U.S. three-day event quad rode races over jumps on the side – Davidson, Kevin Freeman, Mike Plumb and Jimmy Wofford.

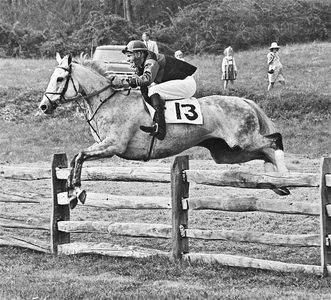

Frank Chapot and Evening Mail (the grey horse) over the 13th fence of The Marland Hunt Cup (Douglas Lees photo from 1973)Six-time Olympian and two-time silver medalist show jumper Frank Chapot placed third twice in the Hunt Cup (1965 on Tall Chief, 1973 on Evening Mail.) Olympic show jumper Kathy Kusner was the first woman to ride in the Hunt Cup in 1971.

Frank Chapot and Evening Mail (the grey horse) over the 13th fence of The Marland Hunt Cup (Douglas Lees photo from 1973)Six-time Olympian and two-time silver medalist show jumper Frank Chapot placed third twice in the Hunt Cup (1965 on Tall Chief, 1973 on Evening Mail.) Olympic show jumper Kathy Kusner was the first woman to ride in the Hunt Cup in 1971.

Bruce Davidson’s son, Buck Davidson, rode races as well, starting in the pony division in 1987 and finishing his 20-race career finishing fourth in the 1994 Radnor Hunt Cup on Castle Keepsake. “You watch the way he goes, the way he rides — he understands galloping a horse,” wrote the senior Davidson. “It is something that the event world needs to learn.

“With the right balance and rhythm and connection you can go the distance and jump the jumps with as little interference as possible.”

Olympic event veteran and thoroughbred breeder Denny Emerson is a fan of the cross-pollination between the two sports.

“There are a few riders who are such athletes that they can rather seamlessly go from one riding sport to another, and can excel in whatever they try,” Emerson wrote in his “How Good Riders Get Good.”

From his Facebook post Denny wrote about position over fences - check out how he describes how Mike Plumb's position over a Maryland Hunt Cup fence is completely appropriate for the situation.

Mike Plumb won the Maclay equitation championships as a junior, won two Olympic team gold medals and rode for the U.S. in seven games.

Mike Plumb on Oliphant,1976 Grand National (Photo by ©Douglas Lees)Plumb rode Oliphant – second to the legendary Fort Devon in the 1976 Maryland Hunt Cup, falling with Koolabah in 1977.

Mike Plumb on Oliphant,1976 Grand National (Photo by ©Douglas Lees)Plumb rode Oliphant – second to the legendary Fort Devon in the 1976 Maryland Hunt Cup, falling with Koolabah in 1977.

Plumb’s father, Charles Plumb, rode the 1929 Maryland Hunt Cup winner, Alligator.

Jennie Brannigan began working with steeplechase owners, thoroughbred breeders and longtime executive-level eventing supporters Tim and Nina Gardner while she was a young rider. Brannigan won team and individual gold in the 2008 North American Young Riders Championship, then worked for Olympic champion Phillip Dutton at his True Prospect, partnering with Dutton on many Gardner homebreds and young stock at their Welcome Here Farm in West Grove, Pennsylvania.

She campaigned two-time horse of the year, Cambalda, and more recently notched a big 4* win at Bromont in June with three-generation Gardner homebred, Twilightslastgleam.

Brannigan won over timber at the Brandywine point-to-point in 2017 with Joshua G. for owner Armata Stable and trainer Kathy Neilson. Joshua G. and Brannigan fell at the sixth while going strongly in the 2017 Maryland Hunt Cup. (photo, above, of the 3rd fence at the 2017 Maryland Hunt Cup. Brannigan and Joshua G are on the far right. ©Douglas Lees)

She grew up near Chicago – nowhere near any steeplechasing, but Brannigan once said in an interview that “if I had known what this was when I was younger, I’d probably have become a jump jockey not an event rider. People have said the time I’ve spent riding racehorses has helped me. I think I’ve gotten a lot better.

“I’ve ridden a lot of (speed work for flat trainer Michael Matz and others), and feel very comfortable at speed now.

“It’s cool to be part of (steeplechasing), historically. The fact that Bruce Davidson and Mike Plumb did it back in the day? That’s something that appealed to me. So many kids now have been brought up to …. perform in an arena. Riding over big timber fences in a group is very different from that.”

(Elite eventer Will Coleman is another strong believer in the steeplechase-eventing link.

One of his best horses, French-bred former steeplechaser Tight Lines was the highest-placed Thoroughbred pair at Kentucky in 2019, 13th.

Coleman and Tight Lines’ partnership began in 2014, when the horse was purchased by Coleman’s connections through Canadian eventer Lindsay Traisnel and her husband Xavier. The rangy gray had competed previously through CCI2*-L, produced by French eventer Paul Gatien in the barn of Nicolas and Theirry Touzaint.

“He’s an amazing galloper,” Coleman told reporters after cross-country in Kentucky in 2019. Tight Lines “tries so much. He’s as enthusiastic at Fence 1 as he is at Fence 31.”

Hear how Kevin Freeman scaled the twin peaks of eventing and steeplechase

For all of his success of three-day eventing, three-time Olympic team silver medalist Kevin Freeman still calls steeplechasing “the most thrilling thing I’ve ever done on a horse.” (Freudy / NSA Archives photo of Freeman riding Stutter Start to win the 1969 PA Hunt Cup)

He’s long retired from the saddle though he stays involved in horses, still teaching a few lessons near his home in Oregon. “There’s nothing more exciting than riding down to a fence with horses on either side of you trying to be the first to the finish line.”

The late Jimmy Wofford, who died Feb. 2, had praised Kevin Freeman as “one of the fastest and smoothest riders” American eventing ever produced.

Freeman was asked to pen the definitive comparison of jump race riding and upper level eventing in author Bill Steinkraus’s 1976 volume, the “U.S. Equestrian Team Book of Riding."

He was born in Portland, Oregon, growing up on a farm in nearby Molalla. He’d learned to love horses and riding when he was young, starting the way many young boys start in equestrian.

“I discovered that the riding academy my sister rode at had a lot of attractive young ladies,” Freeman says with a chuckle at the memory. "That's why I started."

His equestrian education started on the show circuit, competing in hunters and equitation on the west coast, then east coast. He played polo while studying agricultural engineering at Cornell.

Freeman pursued a grad degree at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania.

Freeman’s short steeplechase career had him winning over hurdles and over timber, his biggest win coming in the 1968 Iroquois with Bill Rochester’s Appollon. He won over the Pennsylvania Hunt Cup course with Jill Slater’s Stutter Start, and finished third in the 1971 Maryland Hunt Cup with Morning Mac, behind timber legends Landing Party and Haffaday.

In his other world, Freeman was on three Olympic silver medal three-day event squads – 1964, 1968 and 1972.

Freeman rode 1972 Olympic mount Good Mixture. When asked his impression after his first ride on the horse, he said, "Well, either take him to the ’72 Olympics or the Maryland Hunt Cup.”

Born to it – Jumping in his genes

Buzz Hannum piloted Morning Mac to two Maryland Hunt Cup wins, in 1970 and 1973. ©Douglas Lees

Morning Mac was a Pennsylvania-bred son of stallion Cormac out of the Star Beacon mare, Fairplex. He was foaled in 1962 at breeder Paul Baldwin’s farm.

Cormac himself raced over timber for Gene Weymouth, starting in the Maryland Grand National but pulling up after a career-ending cut to his tendon in the 1949 Maryland Hunt Cup.

Cormac sired steeplechase winners Burnmac, Morning Mac, Fenceador, King of Spades, Eastcor and Red Lion Mike, as well as Olympic champion Bally Cor.

After showing natural jumping talent as a young horse, Bally Cor (registered name, Ballycor) was paired with skilled young rider Tad Coffin. Together, the dream duo won team and individual gold at the 1975 Pan American Games, team and individual gold at the 1976 Montreal Olympics and team bronze at the 1978 World Championships.

Bally Cor produced a thoroughbred filly foal, Bally Thorn by Winged T, who in turn produced a halfbred filly, Bally Mar, 2001 USEA Mare of the Year.

Freeman was inducted into the Oregon Sports Hall of Fame in 1991 and into the U.S. Eventing Association Hall of Fame in 2009.

He’s happy to reminisce about the good old days straddling the steeplechase and eventing worlds. There are comparisons, but there are distinct differences.

“For all their similarities, the two sports really are different,” Freeman says. “Eventing is technically a more difficult jumping sequence than stseeplechase, but you’re racing against the clock, not against other horses.

“I bet Morning Mac would have made a good show hunter – he moved real well, but (Iroquois winner) Appollon is the one I bet would have been a good event horse if he’d gotten that chance. Stutter Start? He’d sometimes hang a leg. I don’t believe I’d want to ride him over a solid course (of cross-country event fences.)”

An excerpt from Freeman’s chapter, “Steeplechasing and Eventing” in the “U.S. Equestrian Team Book of Riding”

“It is hard to equal the thrill of rolling down to a solid timber fence late in a race with one or more other horses at your side.

In the end, it is the fortunate person who has the chance to both race and event.

Such people have it the best of all.

The question is if racing helps you develop as a three-day rider. Steeplechasing … asks different questions. It can help you by making you more comfortable at speed, by improving your balance and by teaching you to listen to your horse more effectively.

But, conversely, it can hurt you if you get into the habit of riding too short or start seeing to many long distances to fences.

The USET three-day coach, Jack Le Goff rode a lot of races in France both on the flat and over jumps before his eventing career. I would always encourage an event rider to ride races … because it’s another kind of riding experience, and it’s so much fun.

Steeplechase … obviously has great relevance around a cross-country course. It helps you to get your horse galloping smoothly and quietly, and thus economically.

Racing and eventing ask different questions of the rider. In an event, you’re alone on the cross-country course, and you’re riding against the clock and against the difficulty of the course. In racing, your only concern is beating the other horses in the race; the clock has little relevance.

The difference even colors your attitude towards a fall. Obviously, nobody likes to fall, but in the cold light of analysis, you must try at all costs – penalties – to avoid a fall in eventing.

In racing, however, it often gets down to the point late in a race when …. you just have to take a chance if you want to win. Not a foolhardy chance, but a calculated one.

There’s no reason it couldn’t happen in reverse – race riders taking up eventing. Eddie Harty rode for (the Irish three-day event squad) before going on to win the Aintree Grand National. Alessandro Argenton of Italy, and Laurie Morgan and Bill Roycroft of Australia, gold medalists at Rome, had outstanding racing careers at home and in England.

Eventing … might not provide a thrill a minute (like steeplechase), but it’s still quite a challenge to produce a good dressage test with the same horse you’ll jump around cross-country and come back in stadium jumping.”

Steeplechase horsemen weigh in on working between the worlds

National Steeplechase champion rider in 1989 and 1993, Chuck Lawrence has a direct tie to the event world.

He rode French-bred Gorky Park to win a 1991 3-mile hurdle handicap at Great Meadow for Virginian Jim Wilson, then trained Gorky Park’s son, Dresden Farm homebred Smart Gorky for owner Wilson to make eight starts on the flat at 3, in 2006.

His first two starts were at hunt meets.

“I do remember I liked him, but he just never turned out to be what we wanted,” Lawrence says of Smart Gorky. The angular bay was fourth at the maiden claiming level three times.

“I’m sure we had him jumping over the (logs and) mulch in the woods” Lawrence says, near his Fair Hill, Maryland training base, though he doesn't recall eyeing the horse as a future 'chaser.

Wilson’s son, Tommy, was a three-day event rider, and with their connections plus the race education and little bit of jumping exposure, they were able to sell Smart Gorky as an event prospect to Middleburg, Virginia upper level eventer Lynn Symansky.

Smart Gorky became “Donner,” and, with the name change came a change in his strike rate. Donner vaulted from the lower levels to the upper, representing the U.S. in two World Championships (2014 and 2018) and completing seven 5* events before retiring last year.

“We were always excited to follow him in his event career,” Lawrence says. “That connection is pretty natural from racing to eventing. Some of the event riders around Fair Hill gallop in the mornings. I think it helps them learn to ride a little shorter, helps their balance, makes them stronger. It can only help.”

Steeplechase trainer Jazz Napravnik is currently focusing solely on eventing and event training, but her first – and true – love, she says, is, specifically, the thoroughbred horse. (photo: Xavier Aizpuru and Jazz Naprvnik after Farah T Salute wins Crown Royal at Callaway in 2010. ©Tod Marks)

“There’s nothing better,” or more athletic, Napravnik says. Second, or third, careers in eventing for retired racehorses, from the flat or from the steeplechase circuit, are only natural. As a working horseman with experience in all three, Napranik says “seeing the potential for a horse as an athlete is … an easy transition. I’m dedicated to the thoroughbred.”

Napravnik rode her first pony race at age 5 at the Far Hills, New Jersey meet. Later, she worked for jump trainers Bruce Miller, Lilith Boucher, Jack Fisher and others. She calls the late Tom Voss “an important mentor in my career.”

She trained steeplechase horses for a while, winning two stakes with distaffer Farah T Salute, and trained on the flat – she started the career of eventual multiple-graded-stakes-winner Page McKenney. With racehorses and sport horses, it comes down to reading your horse.

“As we transition these horses, I try to listen to what they say because the horse always knows best which direction he wants to go.” Page McKenney, for example is one of the nicest ladies’ hunters in her barn since he returned to her shedrow after retiring from racing. It came down to class, Napravnik says. “He was convinced that everyone (at his first Elkridge Harford opening meet) was there to see him. He was like a peacock.

“You’d think with that kind of athleticism, he’d be a natural to have gone the eventing route, but Page thinks dressage should be a speed event. It would not be a good fit.”

Still, like many race trainers, Napravnik says she incorporated a lot of dressage training with her racehorses. “Dressage is a great foundation for all horses,” she says. “It teaches a horse to use less energy to go faster. It’s useful for all of them, just some of them don’t want that to be their chief focus.

“But sometimes they surprise you. I have this spicy mare, Crazy Bernice” that Napranik claimed in 2018. She ran a few times over hurdles – third at Aiken in 2019 (photo, above, of Crazy Bernice and Napravnik in the paddock ©Tod Marks), but injury ended her race career. “She was sharp, super sharp. Dressage was the last thing I thought she’d excel at. But she loves it.

“Once she realized she could ‘show off’ in the ring, she was perfect. She’s doing a first-level musical freestyle now. We put her to a Glenn Miller big band medley.

“With all these racehorses or ‘chasers, it’s a bit of trial and error, a lot of intuition and, mostly, a lot of listening.”

Danny Warrington grew up grew up with a foot in each world - the flat track and eventing, with 'chasing in the mix, near Fair Hill, Maryland riding with the Unicorn Pony Club and Lana duPont Wright. He started foxhunting “on the line with my father” at age 5 with the Lewisville Hunt.

Warrington says “tolerated dressage to be allowed to ride” the elementary level cross-country courses of his youth.

He traded it for the racetrack at 14, working on the Delaware Park backstretch for Gene Weymouth, later riding over jumps for Hall of Famers Jonathan Sheppard, Janet Elliot and more.

He retired from racing in 1997 following the death of his wife, Amanda Pirie Warrington, from a fall in the advanced division at the September 20 Fair Hill horse trials.

“I pretty much checked out of everything,” Warrington says. “Didn’t touch a horse for five years.” Warrington focused his energies on obtaining his Coast Guard captain’s license, teaching scuba diving, skiing and fishing.

One day, predictably, horses came back in his life. A friend invited him to take a ride.

“One jump and it all came back.”

Warrington mounted a brief steeplechase comeback, riding a few races in 2002 and 2003, but he’d gained newfound appreciation for the importance of dressage as fundamental to any horse’s education, and he pursued three-day eventing. Warrington has competed to the four-star level and has trained several horses to the championship level.

“I call myself the accidental eventer,” Warrington says. (photo courtesy of Warrington's Facebook page) “I’ve gotten a lot of event horses that started out on the racetrack or came from the jump race world. Somebody would call me with a ‘chaser they wanted to sell, saying ‘it’s a little too careful’ to make it running over jumps.

“But that’s just the type you want. Careful.

“I still remember something (Hall of Fame trainer) Burley Cocks said when I asked him how he taught all those horses to brush through the hurdles. He told me, ‘you go ‘til you go fast enough that they make a mistake.’

“(Steeplechase national fence) hurdles are forgiving – the faster you jump the more you win. Event fences not so much. You want a horse that’s a little careful. Bold, but careful.”

Same with riders, Warrington maintains. “What (riding steeplechase races) gave me was the seat and the balance to let a horse find his way out of trouble.”

He had to retrain his eye, though, and change his mindset.

“I remember one day schooling at Bruce Davidson’s. He’d set up an oxer, four strides to another oxer. I’d jump in, every time, and go down the line in three.

“Every time.

“Bruce pretty much had to grab me by my bootstrings (to make me) learn not to leave out that stride.

“You change your eye. In jump racing, ‘when in doubt, leave it out.’ Steeplechase trainers teach you ‘chipping in is a sin.’

“But the upper level event horses, you come around a blind corner to an offset angle down a steep hill, you’ve gotta be able to adjust your stride, like an accordion.

“You want the horse to be thinking, to wait for the stride to come to you.”

Warrington and wife Kelli created the LandSafe training method to teach riders – it’s aimed at event riders but the system works for any discipline, including racing – to fall, a tuck and roll movement designed to push the rider away from a rotational fall.

For more than four decades, Tim and Nina Gardner have supported every level of steeplechase and eventing as riders, owners, breeders, patrons and at the executive level of the organizations that operate all three.

Tim Gardner was born in Philadelphia, raised in the Washington, DC, area, son of a high school teacher and athletic coach who later became director of athletics at Georgetown University.

He attended Georgetown University for both college and medical school. He married classmate, the former Nina Hooton.

Nina went on to become a pediatrician.

Tim became chief of cardiac surgery at the University of Pennsylvania in 1993 then medical director at the Christiana Care Center in 2005. He was president of American Heart Association and the Association for Thoracic Surgery.

They moved to Maryland’s Green Spring Valley when both were on the medical staff at Johns Hopkins, he a heart surgeon and eventual president of the American Heart Association, she a developmental pediatrician.

Nina had ridden as a child – “no showing, no formal training, no saddle even.” When their children began riding, the Gardners both embraced the horse sports that are synonymous with southeast Pennsylvania - hunting, eventing, and breeding, both for racing and for sport.

Nina more recently compiled a book of essays, “The Magic of Horses,” documenting the close relationships of upper level riders in many disciplines with the horse that most influenced their careers. Her own story opens the 2021 release – Nina writes of the quarter horse mare, Dark Sunshine, that she got at age 13.

Gardner homebreds Show of Heart and House Doctor both qualified for the 2000 three-day event squad with Australian-born but Gardner farm-based Phillip Dutton. Show of Heart, a multiple winner at the four-star level, was Dutton’s top choice, but he was injured in his last event before the summer games in Sydney.

Younger, less experienced House Doctor had shipped from Dutton’s base at the Gardner’s Welcome Here Farm near West Grove, Pennsylvania “for the experience,” Dutton said in an interview, a lucky thing because he had to step in at the last minute.

Even though the horse was bred to it – a second-generation Gardner homebred, and aimed for it, at age 8 he was the youngest horse in the Sydney Olympics, and he was lacking in four-star cross-country experience.

A 1992 son of Inca Chief out of Gardner homebred Night House Rock, House Doctor was an elegant bay 3-year-old when Dutton had gotten him in for training. He never raced.

“He was the most classic, beautiful Thoroughbred type,” Dutton wrote of House Doctor. “About 16.1 hands and naturally balanced and well put together. In (early) 2000, he was second at the Foxhall Cup CCI3* and selected as my backup horse for Sydney,” a second-stringer for Show of Heart.

“I’d never been so nervous on cross-country day as at the Sydney Olympics, but he stepped up to the plate,” double-clear cross-country, double-clear show jumping, securing team gold for Australia.

Another of Dutton’s top horses has ties to jump racing: Steeplechase trainer Bruce Fenwick helped hook Dutton up with a Virginia-bred son of Across The Field out of the Quadratic mare, Four Flora. Four Across was renamed The Foreman when purchased for Dutton by Annie Jones. The Foreman went on to win the Fair Hill 3*, second in the 4* at both Rolex and Burghley.

In jump racing, the Gardners have been equally successful, top homebreds including Virginia and International Gold Cup winner Bubble Economy (bred in partnership with Rick Abbott, and pictured after his 2010 Virginia Gold Cup win, ©Douglas Lees), freshman hurdle champion (2001) Geaux Beau, timber stakes winner Serene Harbor and winner on the flat, over hurdles and over timber, second-generation homebred Second Amendment. Second Amendment is sired by the Gardner’s own stallion National Anthem.

National Anthem is also sire of Twilightslastgleam, poster-boy for the Gardner breeding program – he’s out of homebred Royal Child, by steeplechase sire specialist, Northern Baby. With rider Jennie Brannigan, Twilightslastgleam won the Bromont CCI4* long format in June, 2022.

A daughter of National Anthem, Amazing Anthem, Nina says is currently “doing the usual thing for us." She won on the flat (Pimlico at 4), over hurdles and is now competing at the intermediate – two-star – level with Brannigan.

U.S. Equestrian Federation eventing owners of the year in 2014, the Gardners were inducted into the U.S. Eventing Association Hall of Fame in 2018. Nina was the chair of the first U.S. Eventing Association Young Event Horse committee formed in 2004.

Tim is co-chair of the USEA Development Committee, a member of the USEA Foundation board and a member of the board of Fair Hill International.

The brief, arranged marriage of ‘Steeplechase and Eventing’ (in magazine-speak)

Joe and Sean Clancy’s Steeplechase Times print version became the Steeplechase and Eventing Times for parts of 2006, 2007 and 2008, when the brothers capitalized on the partnership potential between the two sports.

It was “mainly because we were looking to expand the steeplechase audience a bit and maximize the talents of Joanie Morris, who was working for us at the time,” Joe Clancy explains. “We had a steeplechase section to the publication and an eventing section in terms of news, and tried to find crossover wherever we could while mixing the two subjects in some of the other features like quotes and numbers and shorter pieces.

“It made sense, for a while, and was well-received. But Joanie got a job with the U.S. Equestrian Federation, and it didn't make as much sense for such a small business to try to tackle two sports when one was pretty challenging.

“Eventing has a much larger pool of participants when you consider all the levels and competitions around the country, which was of interest to our advertisers but that also increased some costs as we tried to expand our mailing list, increase our press run and cover a much wider geographic area.”

Three-day event history

Two equestrian events – chariot and mounted races – were included in the ancient Olympic Games from 776 BCE to 393 CE, though it wasn’t until Stockholm, 1912, that the pre-cursor to the classic three-day event (and today’s, related, short-format event) – the “military” – was conceived.

With roots linked to horse-mounted cavalry, the three-phase event was based on military tradition. Until 1948, only male cavalry members were allowed to compete, and it is only over the last 30 years that female riders have outstripped men in numbers of competitors.

Lt. John "Gyp" Wofford was in full military uniform showing Babe Wartham in the 1932 Olympics at Los Angeles. Gyp Wofford founded the U.S. Equestrian Team and his three sons, Jebb, Warren and Jim, were also Olympic riders. Upperville resident Jim Wofford says the original eventing format, designed to test the cavalry mount, was a more complete measurement of a horse's skills.

The military event included three distinct disciplines. The dressage test (then, as now) is a program ride in an arena simulating the elegance and obedience required from a cavalry horse on the parade and review grounds. It tests intricate control and communication required between rider to horse to perform precision maneuvers in the close quarters of battle.

Day two was speed and endurance day, originally five phases, then four – two “roads and tracks”, phase A and C, to tack on miles to test a horse’s endurance. Phase B was a steeplechase, conducted individually but over brush obstacles like (sometimes identical) the steeplechase hurdles used in modern American jump racing. It was timed, the speed around 600 meters per minute – still quite short of even the “two-minute lick” that is the standard measure of working speed for racehorses – about 800 meters per minute.

Phase D of the classic format three-day event was the cross-country jumping test, a timed jumping course to test the event horse’s bravery, boldness and jumping skill even after their endurance was tapped in phases A through C.

Today, the second day of a three-day event – short format, only includes cross-country jumping, still considered a test of a horse’s bravery, speed and stamina. (©Alissa Norman, from the 2021 Maryland 5 Star, of the "timber" fence on the cross country course, a nod to the steeplechase history of the site)

In both classic and short formats, the test was designed, originally, to simulate a mounted military rider delivering a courier message or boldly riding into battle across unknown terrain.

The final test, in both formats, is show jumping over a course of light rails in an arena to verify a cavalry horse’s correct jumping style when measured after the arduous test of endurance the day before.

Subjective scores in dressage are converted to penalty marks, which are then added to mistakes and time faults in the jumping phases for an overall score much like the human triathlon.

Horse-mounted cavalry was used worldwide through much of World War II. After that, eventing – what the military test came to be called – was opened up to civilians.

The expert speaks

One-time steeplechase jockey, lifelong foxhunter and championship event rider and trainer, the late Jim Wofford believed in the strength of the event-steeplechase link.

The modern event is virtually identical to the original military test, said the Upperville, Virginia-based Olympic veteran who died on Feb. 2. But, Wofford explained in a 2021 interview, that over the last 25 years, the second day of the “test” has gone to just the cross-country jumping phase “since most competition venues don’t have land available for a full speed and endurance test.”

The transition inadvertently puffed up the importance of dressage and show jumping, Wofford said, something favoring heavier warmblood breeds over lighter, faster – and, usually, bolder – thoroughbred horses.

The obedience of dressage is key to everything, Wofford explained, though he said eventing was designed to be a complete test of an equine athlete, not just a dressage spin-off.

Wofford said the international equestrian federation – FEI – has toyed with scoring for decades to produce consistent results.

“Here’s my Reader’s Digest version” of what happened, Wofford said. “Your face would drop off if I tried to explain it to you – so the effect is to now, finally, after a lot of to-and-fro, the three phases are basically on a 1:1:1 basis.”